If the eyes are the windows

of the soul, the nose is the cat flap of the imagination.

Smell is the most evocative

sense. If I could show you a photograph of you, opening a Christmas present

when you were five years old, you might say, "I remember that teddy bear.

I wonder what happened to it?" But if you suddenly smell the particular

fragrance of that teddy bear as you unwrapped it, mingled with pine scent

of the Christmas tree and the Chocolate Orange you'd been eating since

dawn - WHAM. A flood of memory engulfs you. You're there, reliving that moment.

(what does this have to do with radio? - ed.)

(don't worry, I'm getting there - me.)

Why does an aroma have the

power to create an experience so completely? One answer may be neurobiological.

The amygdala, a part of the brain involved in processing emotions, is located

close to the top of the nose. And it's next to the hippocampus, which plays a

big part in the function of memory. You can read a proper scientific article

about it here. So, smell stimulates the

imagination to engage us, and that investment by our brain makes us participants rather than observers.

Now, I'm not suggesting

that we listen to radio through our noses. Although I'm not ruling it out,

either. I had an uncle who claimed to get excellent radio reception through the

fillings in his teeth. But he also heard other voices in his head which

probably weren't being broadcast by the BBC, especially the ones advising him

to save the souls of sinners by exposing himself to them on the bus.

But for me, the process of

listening to radio has affinities with the sense of smell. A radio drama, for

example, can summon up an entire world. You may be hearing nothing more than a

voice and a couple of sound effects coming out of a small, tinny speaker, but

they can transport you to distant places and times, and conjure landscapes that

are real even if they're fantastical. They can take you inside the mind of a

character, plunge you into the thick of dramatic action, and engage your most

profound feelings. Radio can liberate your imagination more effectively than any

other medium.

Here's an example. The

Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams was a cult success that

eventually appeared in many formats. But here's the crucial trajectory:

•

It was a brilliant radio series

•

It was adapted into a mediocre TV series

•

It then became an even more mediocre film

The more money they spent,

the worse it got. The radio series was a wonderful journey through a sci-fi multiverse that existed entirely inside your mind. But the physical actuality

of television curtailed the boundless possibilities of your imagination, and

defined every person, place and artefact as this, rather than whatever

my mind's eye can see. The film version simply went to more elaborate

lengths to disappoint you. The playfulness of the radio series depended in part

on the kind of surreal paradox that is killed stone dead if you start taking it

literally. The mind can entertain two contradictory ideas at once, but most

television can only manage one, or less in some cases. As for film, many mainstream movies are now pure spectacle, erecting both a physical and a metaphorical screen between the viewer and any kind of meaningful experience. Audio stimulates

the imagination, spectacle replaces it.

And for a performer radio

is a dream. You don't have to wear makeup or a costume, or even any clothes at

all. Not many people know that most of the classical music presenters on BBC

Radio 3 work in the nude. Probably. Meanwhile, the great advantage of acting on

radio is that you can give a misleading impression of your appearance. I've

done some radio acting, and when people meet

me they're often surprised by how tall they are.

On the subject of the BBC,

it's a fact that while other platforms are growing (especially for podcast), UK broadcast radio is still dominated by the corporation. I don't know if that dominance is

fair, but BBC radio is unique. It's not perfect, and like the rest of the BBC it has a

top-heavy management structure.

|

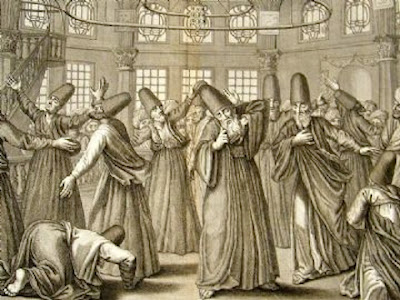

| A typical BBC management training exercise |

Mao Zedong spoke of

Permanent Revolution, and BBC management, fixated on endless assessments,

visions, and indicators, is perpetually revolving around itself like a troupe of bureaucratic dervishes attempting to whirl themselves into a

posture from which they can inspect their own performance in a delirium of

auto-proctology. But the BBC is huge, complex organisation, and that's probably all I can say about it.

As a listener I don't always like the content, and as a writer I'm sometimes

frustrated by the commissioning process. But never mind that. For me, audio at its best can be a

transcendent experience. If you think about the way that something as simple as

a sound coming out of a box can draw you into infinite worlds of endless

possibility, what is that if not a kind of miracle?